Stories

April, 2025

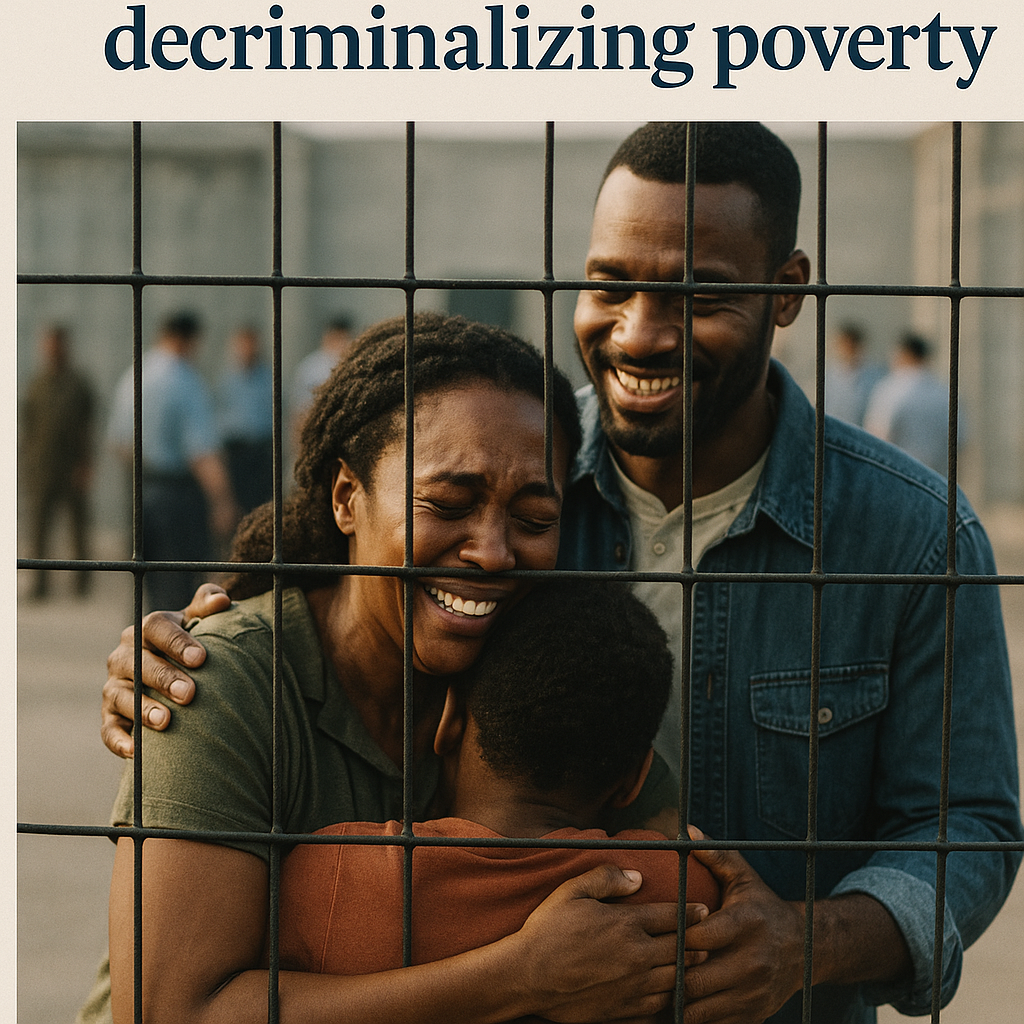

Diversion as a means of decriminalizing poverty

Justice Nest met M.I.[1] in February 2025 at Lang’ata Womens’ remand prison. The remand facility holds individuals who still have active cases in court. M.I. was arrested earlier in the same month and arraigned in court charged with the offence of stealing clothes worth KES 3,000 from her employer.

Let’s take a few steps back and venture into her life. M.I. is not very well educated and comes from a home where her schooling was affected by competing interests against limited resources. At the time of her arrest, she lived in Kibra, a large informal settlement in Nairobi. She has 4 children ranging from 8 years to one-and-a-half-year-old twins.

M.I. would be classified as poor. With little education and/or skills she struggles to find employment and isn’t qualified to do much. It is this state that led her to look for work as a domestic house servant to try and make ends meet and provide for her 4 children. She was arrested while at work and in her defence she says that her employer had given her the clothes since her child had outgrown them. Whether or not her story holds up, it is the items that were allegedly stolen and their worth that inform this article.

R.A.O’s story isn’t too dissimilar from M.I’s. R.A.O[2] is also at Lang’ata Womens’ remand prison. She has been there since December 2024 having been charged in court with the offence of malicious property damage, the allegation being that she had broken a 32’ TV at her place of work where she worked as a barmaid. R.A.O has 2 children aged 9 and 6.

Upon her arraignment at Makadara Law Courts, R.A.O. was admitted to a cash bail of KES 10,000 (about $77[3]) to secure her freedom and continue with her case from the comfort of her home. This amount was subsequently reduced to KES 5,000 ( about $38.5). In both instances, she lacks this amount and her family finds the same inordinately high for them. They are unable to raise the money to secure her freedom.

M.Is and R.A.Os cases are neither new nor unique albeit sad. There are many M.I’s and R.A.Os in Kenyan courts who unfortunately are victims of a system that manifests a criminalisation of poverty.

Their paths are cyclic; a poor upbringing, limited education, economic disempowerment, menial-low paying jobs, crime as a means of fending for family and trying to stay afloat and the criminal justice response that turns a blind eye to anything and everything that has shaped the offender, only focusing on the offence. The 2 ladies’ stories would have been very different if their upbringing was different and if they were able to meet the bond terms. Poverty is an inhibiter, and as a result, their children grow up without their mothers. But where have we failed? How did we get here?

The criminal justice system makes about 4 stops before an individual is arraigned in court; The community, Law enforcement, Prosecution service and The judiciary. At any one of these 4 stops, the actors therein would have responded to these ladies' circumstances differently and stopped criminalising poverty. And they would be doing so whilst acting within the law in a manner that serves justice. Let’s look at all four, shall we?

The community.

The community here refers to where we live and the individual and collective expectations we have as a people. We have become institutionalised to bay for blood and expect the harshest possible criminal justice responses to infringements. If someone offends, let them be arrested and arraigned in court where they shall answer to their charges. The author of this article has had the opportunity to listen, on different occasions, complainants who justify the arrest and arraignment of suspects either because they have had items stolen from them in the past on too many occasions or because the suspect won’t admit to stealing and it’s about time they learnt their lesson by facing criminal trial. Should this be the standard?

Taking the case of M.I. for instance, why would a case where the claim is that the items that were stolen were worth KES. 3,000 end up in court? What is the cost-benefit analysis of investigating and mounting a prosecution for clothes worth KES. 3,000? Perhaps the misguided answer to this lies in focusing on the offence (theft) as opposed to anything else. Is there no one, complainant included, who could have been prevailed upon to consider restitution as a means of justice and resolution of this dispute? Would the complainant suffer any prejudice if they were restituted?

The same argument applies to the case of R.A.O. It is said that she broke a 32’ TV. All factors being constant, is it not possible to give her latitude to replace the TV? Must she be tried in court for this? Must the 2 ladies’ children suffer the pain of having their mothers taken away from them and incarcerated even before a conviction is arrived at and sentence meted out?

This article is not intended to downplay the penal laws currently in place nor trivialise offences, but it calls for an examination of justice responses and interventions to situations where incarceration isn’t the only outcome more so since it results in the criminalisation of poverty. The quest should be the pursuit of restorative justice and not retributive justice. M.I. and R.A.O. are suffering because they are poor. Poverty informed their choices, poverty is keeping them in custody, poverty may determine their outcome and certainly, poverty will shape the lives of their children.

Law enforcement

The function of the police is to maintain law and order. And indeed where a cognisable offence has been identified, to help bring the perpetrators to book. In so doing, the police wield several powers of arrest, investigation and detention. What is often overlooked is their powers in relation to dispute resolution.

Under the policies and regulations for community policing, the National Police Service can devise strategies and activities to engage better with the communities in which they serve. There is no known provision that every incident reported at a police station must be investigated in a manner that leads to prosecution. The police would be acting well within the law, and in a way to improve their relations with the people they serve by distinguishing cases for prosecution and being proactive in those that can be resolved absent of court. As stated earlier in this article, what becomes the cost-benefit analysis of investigating and prosecuting cases such as M.Is and R.A.Os?

The Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP)

The ODPP was created and derives its mandate from Art. 157 of the Constitution of Kenya 2010. ODPP is in charge of all criminal prosecutions in Kenya, save for court-martials, and can INSTITUTE, TAKE OVER and TERMINATE[4] all criminal cases in Kenya. In so doing the ODPP shall not abuse its power and shall have regard to the public interest.

The ODPP has formulated policy instruments which touch inter alia on their relationship with investigators, codes of conduct and ethics, the decision to charge and diversion. These publicly available policy documents provide steps, check boxes and directions that guide and inform charging decisions in Kenya. It should be noted that the ODPP’s Diversion Policy and Guidelines contain comprehensive provisions on when diversion as an alternative to prosecution can be pursued. Yet despite clearly articulated provisions, M.I. and R.A.O. are in court for stealing clothes worth KES 3,000 and breaking a 32’ TV respectively. One wonders then, for instance, if a suspect cannot be diverted and allowed to pay back KES 3,000 worth of stolen clothes, who shall?……who shall?

The decision to charge falls squarely on the ODPP and on this one for these 2 ladies and many like them, the ODPP didn’t HAVE TO charge them. This article does not say they shouldn’t, it makes the argument that they didn’t have to charge for these types of infractions.

M.I. and R.A.O. are poor. They do not have legal representation, are not lawyers themselves, and are unaware that they can challenge the decision previously made to have them charged. The ODPP can terminate cases they had earlier authorised for prosecution. There are review mechanisms for that. They can have their cases diverted and other options pursued. These options ARE still just and justice will be served.

Being poor and unaware of these provisions and avenues available M.I., R.A.O and the many they represent continue to stay in remand, and we, as a system continue to criminalise poverty.

The Judiciary

They sit and serve as independent arbiters of disputes brought to them. Their actions, conduct, processes and decisions emanate from the Constitution which provides for alternative mechanisms for dispute resolution. Indeed and in furtherance of this, the judiciary runs an Alternative Justice System program as well as an annexed Mediation program both of which are intended to deliberately and intentionally deflect litigants from the court system and help them arrive at just conclusions to their matters outside of mainstream litigation. Both are active, and both are managed by judicial officers, I would think that either one of them could and should apply to M.I. and R.A.O…….. but they don’t.

Instead, M.I. and R.A.O. are being prosecuted for cases that have legal, legitimate options available.

This article rests on the unnecessary criminalisation of poverty. I say unnecessary since, in addition to deviance from mandates and policy instruments of justice actors, there have been examples in the past where sentences have been informed by or altogether avoided through the adoption of legal provisions and reasoning or indeed enforcement of statutory provisions. I provide 2 examples, at the very least.

In the case of R vs Thomas Gilbert Cholmondeley where the accused person had been charged with the offence of murder, the allegation being that he had shot and killed KWS ranger Samson ole Sisina in April 2025, the convict offered monetary compensation as well as financial support to the family of the deceased ranger and the sentence considered this[5]. Suffice it to say that the same accused person had also been charged with a similar offence where it was stated that he had shot and killed Robert Njoya Mbugua. This was downgraded to Manslaughter where he was found guilty and sentenced accordingly. The point here is that since Mr Cholmondeley was a man of means, he was able to get the benefit of a system that allowed his financial status to inform the outcome of his case. M.I. and R.A.O. are ‘men’ of straw. Their poverty equally stands to inform the outcome of their cases only that this time it’s not in their favour.

A look at S.51 of the National Cohesion and Integration Act[6] presents a second look at this inequality and the criminalisation of poverty. The section states that ‘The Commission shall make all reasonable endeavours[7] to conciliate a complaint referred to it under S.49 and may, by written notice, require any person to…’

To have an act of parliament be so intentional and deliberate to the extent that when it comes to enforcement, an institution is mandated to ‘make all reasonable endeavours’ concerning conciliation is hard to miss. It doesn’t escape attention that the greatest violators of the Act are politicians and politically exposed persons, who are by no means poor. M.I and R.A.O sadly do not have such explicit provisions that tell actors within the criminal justice system that they are mandated to do everything possible to see that having stolen clothes worth KES 3,000 and broken a 32’ TV we should reconcile or otherwise arrive at a determination in their favour where they avoid prison. Such is the fallacy of our responses.

M.I. and R.A.O. may be poor, but they deserve no less justice, response and speed of action than anyone who is less poor does. Kenya spends an estimated KES 5.5 billion annually or KES 270 daily to feed inmates within its correctional facilities[8]. Considering that around half of the prison population are remandees, this presents a huge cost that goes towards the sustainance of M.I, R.A.O and many others like them for infractions and offences that can best be settled out of court. Let’s keep them out. Let’s not criminalise poverty, we can use diversion to decriminalize poverty.

[1] Name witheld to protect her identity

[2] Name witheld

[3] As per the Central Bank of Kenya’s data on 22nd April 2025

[4] Termination is done with the leave of the court

[5] https://nation.africa/kenya/counties/nakuru/cholmondeley-family-bows-to-pressure-offers-compensation-for-slain-ranger-1231852

[6] Available at www.kenyalaw.org/kl/fileadmin/pdfdownloads/Acts/NationalCohesionandIntegrationAct_No12of2008.pdf

[7] Emphasis is author’s own

[8] https://nation.africa/kenya/news/as-prisoner-feeding-costs-hit-sh5-5bn-is-plea-bargaining-the-solution—3694924 published on 26th January 2022

Eddie Kaddebe